Plant an edible forest garden

Forest gardens combine fruit and nut trees, shrubs, herbs, vines and perennial vegetables to create low maintenance food production systems. The crops reduce food miles, trees and soil absorb carbon and the forest is resilient to flood and drought. Altogether, a brilliant response to climate change.

What is a forest garden?

Forest gardens are food-producing systems which seek to emulate natural woodland ecosystems as closely as possible. They consist of mainly perennial plants which are agriculturally productive or useful, growing as they would in the wild.

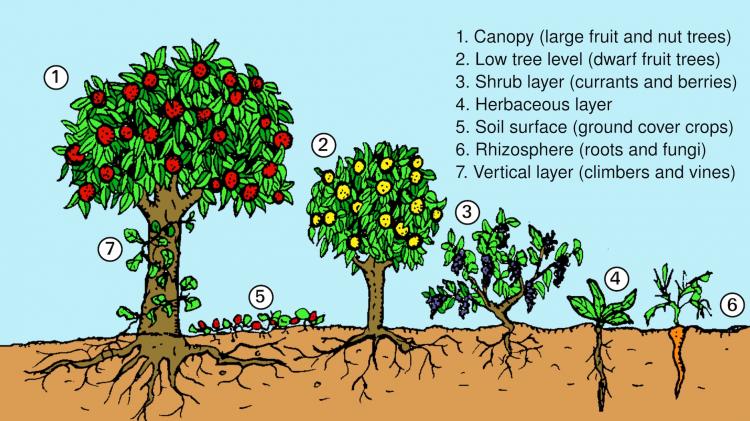

In a forest garden plants are stacked as in a natural forest or woodland. While this structure is universal, each forest or woodland is uniquely composed of species that are specific to its climate and location.

Most temperate forests consist of seven layers of plants (see Graham Burnett's helpful illustration above), while some successionally-advanced tropical forests may feature up to thirteen layers.

The most common seven plant layers are as follows (with examples for forest gardens in temperate climates):

-

Upper canopy (sweet chestnut, cherry, pear, apple, Victoria plum)

-

Lower canopy or sub-canopy (hazel, crab apple, fig, medlar and dwarfing trees)

-

Vines and climbers (kiwi, grape, passion fruit, runner beans)

-

Shrubs, and understorey bushes (blackcurrant, gooseberry, raspberry)

-

Herbaceous perennials and annuals (mint, chives, fennel, rhubarb)

-

Ground cover (strawberries, clover, ramsons)

-

Roots and rhizosphere (Welsh onion, ground nut, garlic and chives, Jerusalem artichoke, fungi and mycorrhiza)

A well-managed forest garden will yield nuts, fruits, herbs and annual crops. Once a forest garden becomes established, it requires little or no input and minimal labour, while continuing to produce harvestable yields.

A short history of forest gardens

Forest gardens are probably the world's oldest form of land use.They originated in prehistoric times along jungle river banks and in the wet foothills of monsoon regions.

Over time, useful tree and vine species were identified, protected and improved whilst undesirable species were eliminated. Forest gardens are still common in the tropics and known as home gardens in southern India, Nepal, and southern Africa; Kandyan forest gardens in Sri Lanka, huertos familiares in Mexico; and pekarangan in Java. These are also called agroforests or shrub gardens. Forest gardens have been shown to be a significant source of income and food security for local populations.

During the 1980s, Robert Hart adapted forest gardening for the United Kingdom's temperate climate. His theories were later developed by Martin Crawford from the Agroforestry Research Trust and various permaculture practitioners including Patrick Whitefield, who wrote How to Make a Forest Garden in 1996. Forest gardens have now been created throughout the temperate world; in America and Australia they are often called ‘food forests’.

Climate change benefits

A well-managed forest garden will yield nuts, fruits, herbs and annual crops, and the reduced food miles of these crops means reduced CO2 emissions. Once a forest garden becomes established, it continues to produce food but requires little or no artificial energy input, no chemical fertiliser or pesticides, and minimal labour, all of which mean lower CO2 outputs.

The trees and soil in the forest garden lock up carbon, just like a natural forest system. 50% of wood is carbon and it is also stored in forest soil. As the trees grow and the undisturbed soil deepens, the amount of carbon locked up increases.

Because most of the plants in a forest garden are perennial and there is such a diversity of different species, they are relatively resilient to the effects of climate change; in seasons when one plant struggles, another will succeed. Trees also protect the soil from erosion by extreme wind and rain events. They provide shade with their canopy, and cool the air through transpiration, creating a local micro climate.

Yields

Graham Burnett has listed some potential yields from an English forest garden. Every country's forest garden is different, but this gives an idea of the huge range and variety of yields possible.

Edible yields: fruit (apples, cherries, currants, gooseberries, grapes, medlars, pears, plums, raspberries), vegetables (Good King Henry, hops, horseradish, Jerusalem artichokes, perennial onions, Turkish rocket), herbs and salads (lemon balm, lovage, mints, ramsons, sorrel, young tree leaves such as lime), nuts and seeds (almonds, hazels, sweet chestnut), mushrooms (lion’s mane, oyster, shitake), beverages (birch sap wine, cider, elderflower cordial, nettle beer).

Non-edible yields: medicinal plants (balms, eucalyptus, periwinkle, St John’s wort, woundwort), fibres (nettles, New Zealand flax), craft and basketry materials (bamboo, coppiced hazel, willow charcoal), building materials, firewood.

Other yields: education, income stream, research data, wildlife, venue for parties, relaxation space, aesthetic and spiritual yields, the list is endless …

Creating a forest garden

Despite the name, forest gardens can be created in modest home gardens, including urban settings. They can also be created on allotments, communal open spaces on inner city housing estates, school yards, and even in containers and tubs on tower block balconies.

Indeed, pioneering forest gardeners have often had limited space; both Robert Hart and Graham Bell used around 0.1 hectares. Although they require some work and money to set up, after a few years require less of both than a conventional garden.

Graham Burnett's beginner’s guide can be found here: The Step By Step Guide to Creating Your Forest Garden

Picture credits: 1) Permaculture Association/Flickr 2) Graham Burnett 3) Permaculture Association

Convert your growing space into a forest garden

Support local growers when choosing your perennial plants

Transform an under-used community area into a forest garden

Support organisations working to protect indigenous forest garden land